(Originally published in Atlantis Rising #31 – January/February, 2002 – and republished in translation in the July/August, 2004, edition of Italy’s Graal Magazine)

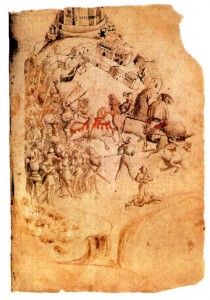

Perhaps no battle in history has been written about more passionately and at greater length than the 1314 Battle of Bannockburn. Without that great battle Scotland may never have managed to shake off the yoke of English domination, may therefore never have established a true national identity, and so would never have birthed the stirring Declaration of Arbroath which was, in the opinion of many, the model for America’s own Declaration of Independence.

No fewer than seven accounts were written within 63 years of the battle, and countless others since. Two were published in the last year alone.

Why all the talk?

Because at the heart of that battle has always lain a great mystery: how the enormously outnumbered Scots could have possibly won the day against a force described as “the greatest army that a king of England had ever commanded.”

To solve that mystery researchers have studied the site’s topography, the political climate, each side’s leadership, and even the height of the tides, to explain how the underdog could have prevailed against such overwhelming odds—yet still the mystery remains. Introduce a possible eleventh-hour intervention of the shadowy Knights Templar into the mix and the mystery only deepens.

But was Scotland really the underdog, or was it only meant to appear so? Working under the credo that what looks too good to be true usually isn’t, I looked someplace new—at the sky above the battlefield—and saw what had perhaps been hidden there, in broad daylight, almost seven hundred years ago.

Let’s go back.

It’s 1286. With the death of Alexander III, Scotland is suddenly without a king. Alexander’s infant granddaughter Margaret, the daughter of King Eric II of Norway, is his only heir, and the Scots quickly swear fealty to her. It doesn’t take long for Alexander’s brother-in-law, England’s crafty King Edward I, to arrange Margaret’s betrothal to his son. But his plans fail when the little queen dies en route.

The throne stands vacant.

Two powerful Scottish nobles, each related by blood to Alexander, vie for the prize. One is Lord John Balliol of Galloway, and the other Lord Robert Bruce of Annandale, grandfather of the man who eventually wins victory at Bannockburn. Civil war seems inevitable. Who to choose?

Incredibly, Scotland asks the king of England to choose, and Edward, true to form, picks the weaker of the two, John Balliol, and is declared superior lord of both realms into the bargain.

With Balliol under his thumb, Edward garrisons Scotland’s castles with his own men. Although not the crowned king of Scotland Edward is, in effect, the next best thing.

But a hero soon steps forward who captures the hearts and minds of the downtrodden. That hero is William Wallace whose exploits, romanticized in Hollywood’s “Braveheart,” are now widely known. Edward eventually has Wallace castrated, drawn and quartered, sending the pieces north as a gentle warning against future mischief.

Enter Annandale’s grandson, Robert the Bruce, who systematically recaptures the strongholds—the exception being Stirling Castle, near Bannockburn.

The Scots lay siege.

Edward’s son, by then King Edward II, is given an ultimatum: Arrive with an army by midsummer day, 24 June 1314, or Sir Phillip de Mowbray will surrender the fortress. Edward accepts the challenge and arrives one day early, with a mighty beast of an army that outnumbers Robert’s by at least three to one.

The situation seems hopeless.

Let’s now look up.

At dawn, in a sky already too bright to see him, Taurus the bull stands on the horizon, facing north. The uppermost stars of Orion the Hunter have just risen. Venus, a planet long associated with the pre-Christian Goddess, shines just north of Orion’s weapon, in a direct line with the bull’s lower horn. The sun rises in Gemini, the heavenly twins, followed by Jupiter, Mercury, and the moon in Cancer. Bringing up the rear is Leo the lion, with the war planet Mars below his breast. Accompanying Orion are his two hunting companions, Canis Major and Canis Minor—the Big Dog and the Little Dog.

Throughout the day this celestial group moves westward. Taurus reaches his zenith at midday, and begins to descend. As evening falls, Orion drives Taurus below the westernhorizon. The sun sets. Night returns. Short as a midsummer night is at that latitude, for those who must fight at dawn it must seem all too long. Many will never see another.

Let’s now consider events at Bannockburn over that same period, keeping in mind the hermetic dictum “as above, so below.” The parallels are striking.

First, an event at midday that becomes the single most memorable of the entire two-day engagement—first blood.

Due to a leadership dispute, Edward’s army is split into two great horns as it thunders near. Earl Gilbert de Clare of Gloucester commands one horn. Earl Humphrey De Bohun of Hereford commands the other.

Some fifty yards ahead of Hereford’s column rides his nephew, Henry de Bohun, “clad in full armor on a powerful warhorse with his spear in his hand.” Henry spots the King of Scots inspecting some of his troops at the forest’s edge armed only with a battleaxe and shield and sitting on a small grey horse. De Bohun sees the chance to singlehandedly win the battle before it begins, and takes it.

He couches his lance and charges, full tilt, towards the Bruce—but the Bruce is ready. A split second before Henry’s lance can pierce him through, Bruce sidesteps his horse and, standing in his stirrups, delivers Henry a mighty blow that cuts through helmet, skull and brain and splinters his axe handle in two.

A tidy tale—stirring enough to survive down through time, as perhaps was intended.

Etymological research reveals that “de Bohun” relates to both Taurus and the word “boun,” the name given to cakes traditionally offered to the Goddess in pre-Christian times. Interestingly enough “bannocks,” as in Bannockburn, are Scottish cakes that were similarly used. In John Barbour’s 14th-century biography of King Robert, Barbour specifically refers to de Bohun and Bruce as “the Boun” and “the Brus,” and I suggest that “Brus” may derive from the Middle English word “brusen,” meaning to crush or mangle. Is it possible that Barbour intended de Bohun’s single-combat with Bruce to symbolize the simultaneous struggle between Taurus and Orion in the sky above? Was he secretly pointing up?

First let’s consider two so-called “myths” about Scotland that refuse to die.

- The Egyptian Connection: The 15th-century Scotichronicon claims that the Scots derive their name from Scota, daughter of the pharaoh who pursued the Children of Israel out of Egypt. Scota and her followers left Egypt shortly thereafter and, after many years, her people eventually settle in a land they name Scotia. It has recently been claimed in Keith Laidler’s The Head of God that Scota’s father was Akhenaten, the pharaoh who tried to establish monotheism in Egypt, using the sun to represent the one true god who should otherwise have had no image. Most astonishingly it has recently been claimed by Laurence Gardner, author of Bloodline of the Holy Grail, that Akhenaten was in fact Moses, the man who led the Isrealites out of Egypt.

- The Jesus Connection: In 1982’s The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail it’s argued that Jesus Christ and Mary Magdalene, contrary to Christian dogma, were married with children, founding a “holy bloodline” that continued to thrive through some of the highest and mightiest families of Europe. Evidence of that bloodline may have been uncovered by the Knights Templar, that mysterious medieval order of warrior monks, while excavating beneath the ruins of Jerusalem’s King Solomon’s Temple in the early 12th century. Upon that order’s barbaric 1307 dissolution, it’s thought that many escaped from France to Scotland, just in time to help Robert the Bruce, a man whose parentage may have united both bloodlines—the Egyptian and the “holy”—in his struggle with England.

Dangerous ideas, indeed—especially in 1314. But, if believed by some, could these ideas have been secretly introduced into the grand tapestry of history as it was woven at Bannockburn, to perhaps one day, in more tolerant times, be trotted out as Truth?

Let’s now consider how those two myths may be connected to another common root—the belief system of ancient Egypt.

In his most recent book, Rex Deus, Tim Wallace-Murphy reports a claim that “Jesus was an initiate of the Egyptian cult of Osiris and a follower of the goddess Isis, which is largely confirmed by the well-documented Templar veneration of Isis under the Christianized guise of the Black Madonna.” It should come as no surprise to readers of this magazine that the belt stars of Orion are central to Graham Hancock and Robert Bauval’s theories about a extraordinarily early groundplan of the pyramids on Egypt’s Giza Plateau.

As I continued to study the “accepted” reasons given for the Scottish victory at Bannockburn, they seemed less and less credible. Moreover, the existence of an underground brotherhood of Scots and English, united in a cause that transcended national loyalty, seemed likely, and confirmation that a secret tale, written deep between the lines of the official tale, began to emerge out of the mists of time.

Some further points of interest:

- In a part of his book dealing with Bruce’s early days, Barbour tells of Bruce being pursued by Lord John of Lorne, using Bruce’s own pair of hunting dogs. Bruce shakes the scent by wading up a stream (just like Orion and his canine companions descend nightly beneath the western ocean, only to rise again with the sun). Barbour also pauses in his tale to deliver a strange discourse on prophecy and the “conjunction of planets,” perhaps to suggest that he was actually telling two tales—one tale above, and one below.

- It has been speculated by A.A.M. Duncan, Barbour’s most recent translator, that Barbour’s patron was Bishop William Sinclair of Dunkeld, younger brother to the Lord of Roslin who was ancestor of the man who built Roslin Chapel, long considered an architectural repository of ancient knowledge and Templar lore.

- As the English army thunders northward, Bruce’s army waits in the Torwood, a forest south of Stirling Castle. Nowadays defined as a hill or heap, there’s an interesting alternative definition of the word “tor” in the 1899 R.H. Allen book Star Names. Referring to the ancient Druids’ reverence of the constellation Taurus, Allen says that it has “perhaps fancifully been claimed that the tors of England were the old sites of their Taurine cult, as our crossbuns are the present representatives of the early bull cakes with the same stellar association, tracing back through the ages to Egypt and Phoenicia.” Perhaps the claim was not so “fanciful.”

- Hereford’s argument with Gloucester about who should lead the advance slows the English such that they must rush to Bannockburn, arriving much tired, yet oh-so-conveniently in the nick of time for Bruce’s midday combat with de Bohun.

- An English deserter named Alexander Seton, a recurring Templar surname, appears in Robert’s camp on the eve of battle. He tells Bruce that de Bohun’s defeat has demoralized the English and that if the Scots fight on the following morning they will surely win. As the dim light of dawn is seen, Seton utters the words “Now’s the time, and now’s the hour,” a phrase immortalized in Scots poet Robert Burns’ stirring ode to Bannockburn.

- In the pre-dawn darkness of June 24 the Scots quietly approach the English army, and succeed in drawing a battleline closer than English prudence should have allowed. As both sides face off, the Scots suddenly kneel in prayer. King Edward thinks they are kneeling to him for mercy while, behind him, Venus has already risen, followed by Orion and the sun. Could the widely reported event have been orchestrated to serve a double purpose—one prayer for the moment, one hidden for posterity?

- Bruce’s greatest military innovation was his unique use of Schiltrons—dense “hedgehogs” of men wielding 12-foot spears pointed outward. Schiltrons had been successfully used before, but only as a stationary defense. Bruce trained his to move, and allowed their offensive use. As Orion’s three belt stars moved inexorably towards Taurus, three Scottish schiltrons advanced on the English. Among the battleflags held aloft was that of Bruce’s trusted lieutenant, James Douglas. It depicted three stars on a skyblue background.

- The English army is positioned in a wedge of land between two tributaries of the River Forth, a tidal river. As the Scots advance into that wedge these tributaries deepen with a tide that is exceptionally high due to the sun and the moon being in such close proximity, giving the English little room to fight except at the front line. Legend then has it that a fresh force of 300 Knights Templar, led by Lord Sinclair of Roslin and followed by an exultant horde of camp followers, come screaming in from the west, throwing the enemy into an irreversible panic. Many drown trying to flee the slaughter. Could that unusual proximity of sun and moon have been known long beforehand? Is that why Edward was given almost a year to assemble his mighty army? And if also known by the Earls Hereford and Gloucester, who had perhaps purposely delayed the English advance, is that why their tired forces bivouacked where they did?

The 1314 Battle of Bannockburn did not end Scotland’s War of Independence, but it did “turn the tide.” In 1322, Edward makes his last foray north and finds the land stripped of sustenance. “King Robert’s Testament,” as Bruce’s scorched-earth policy became known, left behind only a single meal in all the fields in Southern Scotland—one lame cow. There were some in Edward’s retinue who would have quietly snickered!

It’s highly unlikely that mainstream historians will accept as fact any of these connections but, since I have neither academic turf nor reputation to protect, I make them anyway, and welcome debate. But I would caution that further comparison of the written records with the stubbornly persistent myths will reveal other connections too numerous to either list here or shrug off as mere coincidence. There was more going on at the battle of Bannockburn, both above and below, than “history” has allowed—and that’s just the what of it. The why of it’s another tale …

The idea that myth has been persistently used as a vehicle to carry “forbidden” though fundamental truths forward into a more-enlightened future is difficult for many of us to process, and yet it’s important we try—especially on matters of religion, and especially in these terrible times. If it’s possible that all teachings may be equally wrong, and may have grown askew from just a single and sadly forgotten spiritual source more ancient than we’ve been taught, then perhaps “now’s the time and now’s the hour” we began to consider that possibility. To continue to do otherwise has once again proved unimaginably criminal.