(Originally published in Atlantis Rising #57 – May/June, 2006)

Numbered among The New York Times’ top-ten books of 2005, Jonathan Harr’s The Lost Painting describes the search for an Italian Baroque masterpiece by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio that had been missing for centuries. The search for Caravaggio’s “The Taking of Christ” is a fascinating journey through the little-known worlds of art historians, collectors, dealers, curators, and restorers, which alone make Harr’s excellent book well worth the read. But there are other, darker worlds left undiscovered in the book. This article is about those worlds.

I might never have read Harr’s book had a Times review not mentioned that in 1802 a wealthy Scotsman named William Hamilton Nisbet had purchased the painting. Thanks to a personal investigation into the genealogy of my clan, I knew a few things about William that the book does not touch upon–things I will reveal in due course.

But first let’s look at the painting.

Now known to have been commissioned in 1602 by Ciriaco Mattei, one of Caravaggio’s wealthy Roman patrons, “The Taking” depicts the moment Judas betrays Jesus with a kiss, revealing Christ’s identity to the soldiers sent to arrest him.

That Caravaggio had painted such a work was known to scholars through a 1672 description by Giovan Bellori, an art critic who had seen it hanging in Rome.

“Judas lays his hand on the shoulder of the Lord after the kiss,” Bellori wrote, “and a soldier in full armor extends his arm and his ironclad hand to the chest of the Lord who stands patiently and humbly with his arms crossed before him.”

Although it is discussed nowhere in Harr’s book, readers of this article will notice a major discrepancy in Bellori’s description–Christ’s arms are not “crossed before him.” In fact, Caravaggio’s rather bored-looking Christ, one eyebrow raised, appears to be doing little more than cracking his knuckles. To the far-right Caravaggio, in one of several self-portraits, holds up a lantern in true Luciferian fashion as though suggesting that this pivotal Biblical event may have been meticulously planned by the main participant–an idea that has found wider acceptance in the last 40 years than it had back in Caravaggio’s day.

But I get ahead of myself.

In Harr’s book two art researchers, Francesca Cappelletti and Laura Testa, gain rare access to the privately held Mattei archives in order to authenticate the provenance of a painting of St. John the Baptist. While there, they discover a mention of “The Taking,” and follow the painting’s paper trail across two centuries, from the time of its commission until the time it was sold to Nisbet. Along the way they discover a highly flawed inventory of 1793 that switches the painting’s attribution to Gerard van Honthorst, a known Caravaggio imitator.

Laura then discovers Nisbet’s export license in Rome’s Archivio di Stato, which puts the declared value for a six-painting purchase at 525 scudi, the Roman currency of the day.

Later in the book, Francesca makes her way to the U.K., where she finds a 1972 history of the National Gallery of Scotland’s collection, written by then assistant keeper of the gallery, Hugh Brigstocke, which listed a painting named “Tribute Money,” by another Caravaggio imitator named Serodine, as having been “bought as by Rubens from the Palazzo Mattei by William Hamilton Nisbet in 1802.” The Serodine, Brigstocke wrote, was part of a 1921 “bequest of 28 paintings” from Mary Georgina Constance Nisbet Hamilton Ogilvy, the last of William’s direct heirs.

If “The Taking” was part of that bequest, the Scottish National Gallery had let what would become, Harr writes, “the single most valuable painting of the group slip through its hands.” It is not made clear, however, whether the bequest actually included the misattributed Caravaggio. Most likely it did not.

While there are indeed at least two paintings of the original six Matteis currently in the National Gallery’s collection, I have a bit of a problem with Brigstocke’s description of the provenance of Serodine’s “Tribute Money,” specifically his claim that Nisbet had bought the painting “as by Rubens.”

In Nisbet of That Ilk, a genealogical tome written in 1941, I discovered a list of the bequeathed paintings transcribed from the gallery’s 1929 catalog that attributes “Tribute Money” to Jusepe de Ribera, yet another Caravaggio imitator. While I can appreciate that a painting’s misattribution might be discovered and rectified after its acquisition, it makes little sense that Brigstocke’s 1972 history of the National Gallery’s collection says that the Serodine painting was bought as a Rubens while the gallery’s own 1929 catalog indicates it was bought as a Ribera. It is also highly interesting that the research project that initially drew Francesca and Laura to the Mattei archives touched upon a dispute between two respected Caravaggio scholars over the attribution of a pair of almost identical paintings of John the Baptist. One of the paintings, long thought to be by Caravaggio, is later found to have been by Ribera. Jusepe de Ribera, it would seem, was the most accomplished Caravaggio imitator of them all.

I also have a problem with the number of paintings in the bequest. Harr writes that Brigestocke put the number at 28, while the 1929 catalog put the number at 29. There are clearly issues here that should be investigated: the number of paintings bequeathed to the National Gallery in 1921, and the attribution of “Tribute Money” at the time it was bought by Nisbet.

If and when these issues are resolved another “lost” masterpiece is found, I am ready to accept my fair share of the finder’s fee, thank you.

But back to the chase.

Three of the book’s investigators independently find it likely that Nisbet’s Caravaggio was later sold at auction, but none find a record of the buyer. One of the investigators, however, finds an intriguing document in Edinburgh’s Scottish Records Office–a receipt for the six paintings, signed by Duke Giuseppe Mattei in 1802, for 2,300 scudi, more than four times the price declared on Nisbet’s Italian export license. While the vast discrepancy in valuation would have saved Nisbet a tidy sum in customs duties, the misattributions, I feel, would have enabled him to take at least one national treasure out of Italy into the bargain.

Although Nisbet remains a man of mystery throughout Harr’s book, I will now put some meat on his bones.

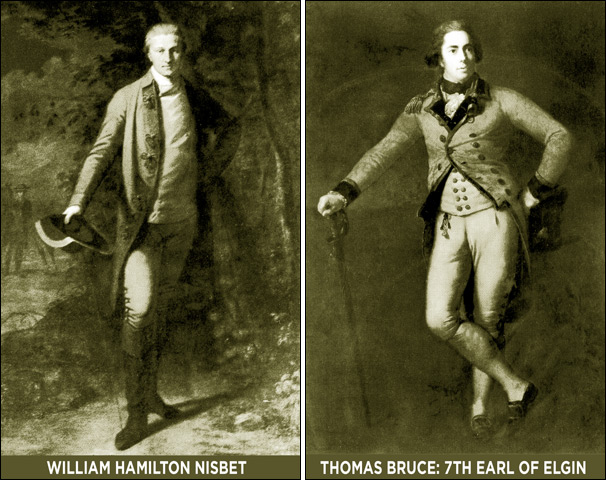

William Hamilton Nisbet was the eldest son of William Nisbet of Dirleton, and Mary, heiress of the wealthy Hamilton family. He incorporated the name Hamilton upon the death of his mother, whose properties he inherited.

William’s only child, another Mary, married Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, in 1799, three years before William purchased the Caravaggio. And while William was striking his bargain with Giuseppe in Rome, Thomas, as British ambassador to Constantinople, was arranging the removal of what have become infamously known as the “Elgin Marbles” from the Athens Parthenon, underwritten in large part by the Nisbet family fortune and fueling a bitter debate between Greece and Britain which has raged ever since. Indeed, the term “Elginism” has become synonymous with the systematic and opportunistic plunder of the antiquities of less-powerful nations by more-powerful nations.

Moreover, while Elgin and his father-in-law were conducting business in Greece and Italy, Elgin’s secretary, William Richard Hamilton, seized custody of the Rosetta Stone from the French following that country’s 1801 defeat at the Battle of the Nile. Key to the deciphering of hieroglyphics, that great prize, along with the Elgin Marbles, is among the British Museum’s greatest tourist attractions, and is still as much a bone of contention with Egypt as the Marbles are with Greece.

Quite the family business.

While British Admiral Horatio Nelson’s victory at the Battle of the Nile greased the way for Elgin and his secretary to get the political leverage necessary to dismantle the Marbles from the Parthenon and relieve the French and the Egyptians of the Rosetta Stone, Napoleon’s 1798 occupation of Italy, on the other hand, had put the economic squeeze on many of that country’s wealthier families, forcing them to pay for the upkeep of the occupying army. It is at this point that the material wealth of the Mattei family begins to diminish, and just three years later William Hamilton Nisbet shows up with his moneybags and strikes a bargain for “The Taking of Christ” and five other paintings.

Could it be possible that the aforementioned highly flawed inventory of 1793, which misattributed so much of the Mattei collection, had been compiled in anticipation of Napoleon’s occupation and ultimate defeat, with the knowledge that molti scudi would soon be forthcoming from Britain?

It follows that there is another interesting bond between Elgin and his father-in-law that begs our attention and, given an admittedly speculative clandestine connection between all adversaries during the Napoleonic Wars, it should not be taken lightly.

William Hamilton Nisbet’s father was the 11th Grand Master of Scottish Freemasonry in 1746, and Lord Elgin’s grandfather Charles was the 23rd GM during 1761-63, the first GM to serve what became the customary three-year term. The significance of this relationship should become more apparent as we focus our attention on the Italian contingent of the Caravaggio saga.

I have little to say about Giuseppe Mattei, the man William bought six paintings from in 1802, except that he wrote two receipts–one for William to take home to Scotland, and one for the customs man–and furnished some form of documentation that considerably downplayed the true value of the paintings.

As the man who originally commissioned “The Taking,” however, Giuseppe’s ancestor Ciriaco deserves a closer look. Like the Freemasons, Ciriaco Mattei seems to have held a considerably more than pedestrian interest in Egyptian symbology. Indeed, his garden was graced by the only privately owned Egyptian obelisk in Rome, first raised by Rameses II in Heliopolis and brought to Italy during the Roman occupation of Egypt to be erected at a temple to Isis, the Egyptian goddess who weaves her way in and out of freemasonic lore. It is for Ciriaco that Caravaggio paints one of several depictions of John the Baptist, patron saint of both the freemasons and the Knights Templar, arguably the progenitors of the Freemasonic brotherhood. Interestingly, his “Beheading of John the Baptist” was commissioned by the Knights of Malta, a Catholic chivalric order similar to the Templars that Caravaggio was initiated into just two years before his death, and is the only painting Caravaggio is known to have signed, intriguingly placing his signature in the Baptist’s pool of blood.

Ciriaco was the brother of Cardinal Girolamo Mattei, one of several cardinals to also commission works by Caravaggio. Considering the rather revisionist Christian imagery to be found in “The Taking” and other works, it is surprising that Caravaggio’s talents would be much in demand by such princes of the church–and yet they were.

Let’s take just one other Caravaggio, “The Penitent Magdalene,” as an example.

The repentant Mary Magdalene was a popular subject of the day, but Caravaggio’s version should have been recognized as heretical, especially by the man who commissioned it–a Catholic Monsignor named Petrignani.

The painting shows a young girl seated on a low stool, one tear running down her cheek, with her hands in her lap. Once again, as in “The Taking,” it is the hands that give the telltale clue something is amiss here.

The painting shows a young girl seated on a low stool, one tear running down her cheek, with her hands in her lap. Once again, as in “The Taking,” it is the hands that give the telltale clue something is amiss here.

Unlike most of his contemporaries who drew their compositions from their own imaginations, Caravaggio used live models while working, He therefore became a master at depicting naturalistic poses, and so it is surprising that in this painting Mary Magdalene’s hands do not seem to be naturally placed in her lap, unless Caravaggio had instructed his model to pretend she is cradling a baby. Mary has also set aside the jewelry a baby might grab, and even has on her lap a baby’s support cushion.

Who would be the likely father of this invisible baby? Well, if we are to believe assertions put forth in such blockbusters as Holy Blood, Holy Grailand Dan Brown’s more recent Da Vinci Code, the most likely candidate would be Jesus, himself–a theory that contradicts two-millennia of Catholic dogma, but which continues to gain ever more purchase in the popular imagination. If true, could it be that Caravaggio’s painting was meant to show a 16th-century Mary Magdalene mourning a child who had been written out of history for the previous 1600 years?

Whether such a composition was Caravaggio’s vision or the vision of Monsignor Petrignani is a question well worth asking, and there are certainly “alternate” paths of historical inquiry that will suggest that at the upper levels of the Vatican a suppressed history of Jesus and Mary Magdalene had always been known, but had not been considered a good fit with the church’s scrupulously-considered and ongoing business plan.

You might well wonder how evidence of such a huge secret, if true, could possibly be kept hidden by so many for so long. The answer to that question may be that it has not been kept hidden; at least from “those with eyes to see,” because it’s known that the vast majority with eyes that cannot or will not see has always ignored the same evidence.

Caravaggio was neither the first nor last painter to pictorially suggest that Mary Magdalene and Jesus may have had children. Just one example can be found in the right-hand panel of the “Portinari Triptych,” painted by Hugo van der Goes over a century earlier. Mary is the woman in white holding the jar. Saint Margaret of Antioch, patron saint of pregnant women, tellingly stands by her side. On display at the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence, countless visitors continue to view the painting annually without giving Mary’s spectacularly distended abdomen a second of serious thought.

Caravaggio was neither the first nor last painter to pictorially suggest that Mary Magdalene and Jesus may have had children. Just one example can be found in the right-hand panel of the “Portinari Triptych,” painted by Hugo van der Goes over a century earlier. Mary is the woman in white holding the jar. Saint Margaret of Antioch, patron saint of pregnant women, tellingly stands by her side. On display at the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence, countless visitors continue to view the painting annually without giving Mary’s spectacularly distended abdomen a second of serious thought.

As previously mentioned, Bellori’s description of “The Taking of Christ” is woefully deficient when it says that the arms of Jesus are “crossed before him.” A 1999 article in the Catholic Herald describes Christ’s hands as being “folded in a gesture of submission” and, although a tad closer to the mark than Bellori’s description is still a far cry from the interpretation that Caravaggio’s composition begs upon viewing, no?

On February 17, 1600, Caravaggio’s Vatican patrons watched a Dominican monk named Giordano Bruno burn to death in Rome’s Campo dei Fiori. Giordano, an exiled Dominican monk, had the temerity to agree with the Copernican view that asserted the earth rotated on its axis once daily and traveled around the sun once yearly–an argument that subverted, too soon, a timeline of discovery perhaps already long set by the cognoscenti.

It is only nowadays that Bruno’s true danger to the “spin” of his day can be recognized for what it was, and what it continues to be–the danger that the unwashed masses might occasionally become inclined to think for themselves.

“Who so itcheth to Philosophy,” Bruno said, “must set to work by putting all things to the doubt.”

Amen!