(Originally published in Atlantis Rising #65 — September/October, 2007 — under the title “The Rosslyn Motet: What the Mainstream Media Didn’t Tell You about the Chapel’s Musical Cubes,” and republished in translation in the December 2007 edition of Italy’s Hera magazine.)

On April 30, 2007, Scotland’s newspaper of record, The Scotsman, published a short article headlined “Musical Secret Uncovered in Chapel Carvings,” about a father-and-son team of Edinburgh musicians, Tommy and Stuart Mitchell, who claimed to have “found a secret piece of music hidden in carvings at Rosslyn Chapel.” It was, Stuart said, like finding a “compact disc from the 15th century.”

Two weeks later, after the story had been picked up by the BBC, the AP and Reuters wire services, such high-profile newspapers as the New York Times and the Boston Globe, and the enthusiastic participation of internet bloggers everywhere, the Scotsman article had circumnavigated the globe, just in time for the May 18 world premier of the musical piece the Mitchells had titled “The Rosslyn Motet,” performed in the chapel that The Da Vinci Code had made famous.

Despite the fact that when the final notes of the Motet had been played the chapel had resisted, contrary to the expectations of many, giving up even one of its long-speculated secrets, the commercial success of the composition had been assured, and the product made available to shoppers around the world. Three more performances of the piece were quickly scheduled at Rosslyn and, by month’s end, a Google search of “Rosslyn Motet” netted an astounding 17,300 hits.

But the story about the discovery, already dubbed “The Holy Grail of Music” by the Mitchells, themselves, was not a new one, and was far from complete.

I first read about Stuart Mitchell 18 months earlier in an Oct. 1, 2005, Scotsman article titled “Composer Cracks Rosslyn’s Musical Code.” The article reported that Stuart took “20 years to crack a complex series of codes which have mystified historians for generations,” and that “his feat was hailed by experts as a stroke of genius.”

“The codes were hidden,” the article continued, “in 213 cubes in the ceiling of the chapel, where parts of the film of Dan Brown’s best-seller The Da Vinci Code were shot this week.”

I immediately posted a lengthy list of cautions about the claims put forth in the article to the Sinclair Discussion Group, a worldwide network connected, by blood or by interest, to the chapel’s founder, William St. Clair. One of those cautions was simply that the hailing “experts” touted in the article were represented by just one—James Cunningham, author of “The Medieval Diatonic Scale,” who said that it was a “stroke of genius to have discovered the cadences which inspired the music.” I told the group that a Google search for Cunningham and his tome would garner zero results—and except for results now connected to me, it still does.

Over the next 18 months, including the article that set the alternate history world on fire, the Scotsman published three more articles about Stuart Mitchell.

In the first of these articles, the April 27, 2006 “Tune in to the Da Vinci Coda,” Stuart’s father Tommy is introduced to us as the man who “spent 20 years cracking this code in the ceiling.” Stuart is now described as “orchestrating” his father’s finding for “The Rosslyn Motet.”

It is in this article that we get the first quasi-comprehensible description of the chapel’s hidden code, and how it was unraveled. I will try to make it better than it was.

At one end of Rosslyn Chapel is an area known as the “Lady Chapel,” the ceiling of which is supported by arched ribs reaching out and under it from the three pillars to its immediate west and the wall to the east.

From these ribs hang what have become known as the “Rosslyn Cubes,” and among the 213 existing cubes (two are missing) can be found 13 uniquely different carved patterns. Tommy’s breakthrough, the article says, came when he “discovered that the markings carved on the face of the cubes seem to match a phenomenon called Cymatics or Chladni patterns,” caused when a “sustained note is used to vibrate a sheet of metal covered in powder, producing marks.” The marks produced by different notes can “include flowers, diamonds and hexagons—shapes all present on the Rosslyn cubes.”

Believing that the similarity of the Chladni patterns with the carvings on the Rosslyn cubes was “beyond coincidence,” Stuart assigned a note to each of the 13 carved variations and, according to the article, is now “orchestrating the findings for a new recording called The Rosslyn Motet.”

It is the Mitchells’ hope that the music, as the article says, “when played on medieval instruments in situ, will resonate throughout the chapel unlocking a secret in the stone.”

As we now know, that did not happen. But with the well-timed assistance of the global media, combined with a public interest in all things Da Vinci and Rosslyn, it hardly mattered. The commercial success of the Motet was orchestrated to be a fait accompli, and it was.

Readers of the four Scotsman articles about the Motet, still available in the newspaper’s online archive, might find it curious that in none of them is Tommy Mitchell specifically credited as the “composer” of the piece, which we now know him to be. This is perhaps because by the time the third article had been written the newspaper had already produced, and would soon offer to its readers on May 15, 2006, the first podcast in a five-part Rosslyn Chapel series, meant to raise the paper’s profile in international cyberspace. Each of these five podcasts uses the Motet as its soundtrack, and lists Stuart as the composer in its end titles. It is inconceivable to me that after three articles and five podcasts the Mitchells would not have pointed out the paper’s error, and yet it seems they didn’t. The short Scotsman article that went round the world on April 30, 2007, still did not substantively contradict any part of its previous reports, but it is very interesting to those of us who notice such things that the newspaper has not touched the story since—not even to review the May 18 concert held just a few miles south of the paper’s Edinburgh headquarters.

But the story of the Rosslyn Cubes did not begin with the Mitchells.

As early as June 2002 the Scotsman had already published an article about the mystery of the cubes, and mentioned within it a name that might ring some bells with alternate history enthusiasts—Stephen Prior. A co-writer and researcher with the well-known writing team of Clive Prince and Lynn Picknett, this former head of the parapsychology division of the British Secret Service was, at the time, running the day-to-day operations of a hotel in Gullane, Scotland, named The Templar Lodge. Under Prior’s stewardship the hotel hosted, until his untimely death from a particularly aggressive form of cancer, several successful confabs of such “fringe” historical research groups as the Sauniere Society.

As far as the Rosslyn Cubes were concerned, it seems that Prior sincerely believed that the cubes could, as he says in the article, “hold the key to a health-giving chant from the Middle Ages,” and had already set in motion certain initiatives to finding that key, including commissioning a photographer to record every different variation in the carvings. He was also supplying a CD of those photographs to anyone who would like to look for that key. To sweeten the pot, Prior was offering a hefty monetary prize to the lucky code-breaker, a prize set up in the name of Clementina Bentine, widow of the UK’s famous “Goon Show” alumnus, comedian and author Michael Bentine who, shortly before his death, was made an honorary member of the modern order of the Scottish Knights Templar.

Three years later, in the Scotsman article that gives Stuart Mitchell sole credit for cracking Rosslyn’s musical code, Stuart claims that he “took photographs of the cubes and broke them down into sections.” Actually the photographs the Mitchells use in their YouTube Chladni pattern demonstrations are the same photographs commissioned by Stephen Prior, and the person who performed the Herculean task of mapping the layout of the cubes is a talented musician by the name of Mark Naples, a friend and associate of Prior at the time. Naples, incidentally, sings the vocal tracks on the only album of music actually recorded beneath the cubes of the chapel, “The Roseline Connection,” the title of which relates to the Scottish leyline subsequently made much of in Dan Brown’s blockbuster.

And then there is Brian Allan, author of the book Rosslyn: Between Two Worlds, who has also investigated the cubes/music connection. In a Feb. 8, 2006 article on the SacredFems blog, attributed to an earlier article in the London Sunday Herald, Allan says, “I think the true secret is not the musical score. I think what the cubes represent is something called the Devil’s chord, which is in fact an augmented fourth.” A low frequency sound in the range of 80 to 110 hertz, the Devil’s chord was outlawed by the Catholic church in the middle ages under the belief that those exposed to the chord would begin to enter altered states of consciousness. Allan believes that Rosslyn’s architect, William St. Clair, might have “felt an antipathy to the church which he couldn’t express openly—hence he might have done this in a manner that wouldn’t have been detected.”

In a subsequent Scotsman article, “Tune Into the Da Vinci Coda,” a careful reading makes it obvious that Stuart Mitchell was presented with Allan’s theory, although Allan is not mentioned within the body of the article, giving the article a bit of a disconnect that most readers would not notice, but offering Mitchell the opportunity to say that “In the ceiling is this jump of an augmented fourth, in fact [the music] opens up with an augmented fourth.”

The Mitchells’ first Eureka moment on their path of discovery came when Tommy recognized that the patterns on the cubes were strikingly similar to patterns discovered by German physicist Ernst Chladni in the second half of the eighteenth century. The Mitchells then hypothesize that Chladni’s patterns must have already been known by the fifteenth century and, on the basis of the layout of the 13 distinctly different patterns on 213 cubes, with only two cubes missing, are able to reconstruct the melody that has been hidden there for over 500 years.

In the spring of 2002 I attended an exhibit at Edinburgh’s National Galleries of Scotland titled “Rosslyn: Country of Painter and Poet,” and purchased the exhibit’s handsomely printed program. On page 51 are two remarkable lithographs by Samuel Dukinfield Swarbreck which show that in 1837 there were many more than just two cubes missing, throwing into doubt the 15th-century origin of the Mitchells’ composition if it was based on the layout we now see at Rosslyn. [These lithographs can be seen at the beginning of this article, and can be enlarged for closer viewing].

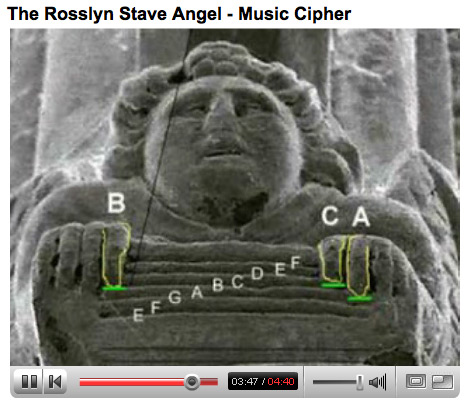

More intriguingly the Mitchells’ second Eureka moment came when they discovered what they have dubbed the “Stave Angel.” Mark Naples, in the description of his 2001 layout, cautiously suggests that this particular angel may be holding a “zimbala or portable organ.”

The Mitchells are not so cautious. This angel, they say, is holding a stave of music, and is pointing to notes on the stave that exactly correspond with the Chladni patterns shown on the first three cubes above the angel’s head and, astonishingly, that these three notes account “for 70 percent of the entire cube sequence.”

The Mitchells are not so cautious. This angel, they say, is holding a stave of music, and is pointing to notes on the stave that exactly correspond with the Chladni patterns shown on the first three cubes above the angel’s head and, astonishingly, that these three notes account “for 70 percent of the entire cube sequence.”

A close inspection of one of the Swarbreck lithographs shows that in 1837 the cubes above that angel were already missing and, indeed, the balance of the arched rib was also missing. Additionally, the shadow next to the angel’s right hand indicates that the hands Swarbreck depicted were not holding a musical stave but were, in fact, raised above an instrument being played on the angel’s lap.

The restoration of the interior of Rosslyn Chapel finally got under way in 1861, a quarter-century later, under the direction of architect David Bryce.

Are we now to believe that Bryce had a reproducible example of every cube that had been broken off in the four centuries since the chapel had been built, including the three that account “for 70 percent of the entire cube sequence,” as well as a schematic that enabled him to recreate the original layout planned in 1446, so that the Mitchells could announce the cracking of the hidden code in 2005?

Are we now to believe that Bryce had a reproducible example of every cube that had been broken off in the four centuries since the chapel had been built, including the three that account “for 70 percent of the entire cube sequence,” as well as a schematic that enabled him to recreate the original layout planned in 1446, so that the Mitchells could announce the cracking of the hidden code in 2005?

There are those who will certainly bring that argument to the table, and point to the fact that Bryce was a Freemason to whom such knowledge could certainly have been imparted by his St. Clair employer. There are also those who will argue that Bryce, because he was a Freemason, might have played a little fast and loose in his restoration, making changes to the architectural fabric of the chapel that would eventually connect its iconography to occult knowledge, and tie the relatively modern Freemasons to the medieval Knights Templar in ways that the chapel’s founder had never intended.

I am happy to let both sides duke that debate out, and am satisfied to say just this:

Rosslyn Chapel, in my studied opinion, continues to be a place of great mystery that has yet to give up its secrets in any way that transcends speculation—including my own. There is a preponderance of oddities about the place that make it one of the most mysterious places on Earth, not the least of which is the importance of the chapel’s geographical location, elegantly described in Scott Creighton’s recent book, The Giza Oracle, and in my previous articles about the chapel.

The above would imply to many observers, that—contrary to what he says in the Oct. 1, 2005, Scotsman article—Stuart Mitchell may not have photographed the Rosslyn Cubes himself. Moreover, one may be forgiven for suspecting, that, in fact, those photos were actually downloaded from Mark Naples’ website for use in Mitchell’s YouTube video, “The Stave Angel,” which shows images of only 11 of the 13 patterns. It is important to note that on Naples’ website only 11 patterns are shown.

The evidence also suggests that Mitchell may very well have utilized Naples’ 2001 layout of the cubes. As the accompanying screenshots show, it appears that Naples’ simple freehand drawing has merely been dressed up for website presentation, albeit without giving credit to the source. Although it appears that, in the probable rush to publish, several mistakes were made, possibly the most suspicious could be this: Naples’ misspelling of the word “Altar,” is also included.

Finally, on Stephen Prior’s now defunct website there was an article titled “The Rosslyn Chapel Cubes Quest” which presented, at some considerable length, the possible connection between the cubes and the Chladni phenomenon. That article has also been archived on Naples’ website since Prior’s death in 2003.

There’s an old saw that says “a lie can be half way around the world before the truth has got its boots on.” Of the only words carved within the chapel, taken from the Old Testament Book of Ezra, the last three might rather mitigate the idea that any falsehood about the chapel can long survive: “Truth Conquers All.”