(Originally published in Atlantis Rising #76 – July/August, 2009. Note that any graphic mentioned, but not shown in the following article, can be viewed within the body of my original 2002 article, “The Pyramids of Scotland,” which can be read in my Articles Archive.)

The Internet has become the long and investigative arm of Everyman, and in no field of inquiry is this more apparent than in genealogy. The new breed of genealogical cybersleuth has shown that ordinary people share an abiding interest in their past, where they came from, and how they got where they are today.

If societies are the sum of their parts, we might then assume that the ancient Egyptians entertained those same motives when they built their pyramid complex at Giza exactly where they did.

But first, lets go to a more recent time.

On February 11, 2009, several UK newspapers reported that the Israeli “spoon bender” of the 1970s, Uri Geller, had purchased Scotland’s tiny Lamb Island, and that my 2002 Atlantis Rising article, “The Pyramids of Scotland”, had inspired the purchase. It was enough to create a huge increase in my website traffic, and to waken my article from its seven-year slumber.

On February 11, 2009, several UK newspapers reported that the Israeli “spoon bender” of the 1970s, Uri Geller, had purchased Scotland’s tiny Lamb Island, and that my 2002 Atlantis Rising article, “The Pyramids of Scotland”, had inspired the purchase. It was enough to create a huge increase in my website traffic, and to waken my article from its seven-year slumber.

Lamb Island, a.k.a. The Lamb, sits about a mile from the seaside town of North Berwick, and was the central island of three that I claimed mirrored the layout of the belt stars of the constellation Orion, which, according to the hotly debated Orion Correlation Theory, were also mirrored in the layout of the “Gizamids.”

I had demonstrated how Orion’s stars, acting with Sirius, an important star in Egyptian cosmology, dictated the locations of several sacred sites connected to the Knights Templar, the order of warrior monks exterminated in 1307 for reasons that still spark controversy. One of those sites, Rosslyn Chapel, would later capture worldwide attention in Dan Brown’s “The Da Vinci Code.”

The correlation also showed connections with Tara, legendary seat of the High Kings of Ireland, and with Dunsinane Castle, one-time repository of Scotland’s Stone of Destiny, the fabled stone thought to have been brought to Scotland by followers of Egyptian Princess Scota, a legend told by Walter Bower, Abbot of Inchcolm, in his 15th-century history, “The Scotichronicon.”

Academics dismiss that legend as a tale fabricated to give Scotland’s monarchs an ancient lineage, and ignore such discoveries as the UK excavations of Egyptian artifacts, the superabundance of a common strain of Mitochondrial DNA in both regions, and a Bradley University report claiming that Egypt imported certain construction techniques from Scotland. Moreover, the Scotichronicon is not the legend’s only record. Travel writer William Dalrymple claims that a letter to Charlemagne from English scholar Alcuin refers to the Scots as “Pueri Egyptiaci,” the Children of Egypt, and author Ralph Ellis traces the story’s origin back farther, to Manetho’s 300BC “History of Egypt.”

But I’ve discovered much more.

Walter Ferrier, in his 1980 “The North Berwick Story,” explains the etymology of the town’s name, writing that Bere is the Old English word for “barley,” and Wic means “village.” In “Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning,” Richard Hinckley Allen reports that in the Egyptian “Book of the Dead” Orion was known as Smati-Osiris, the Barley God.

In my article I drew attention to a mid-17th-century map on which The Lamb was named Long Bellenden — curious because it is the shortest of the three islands. I then speculated that the islands may have been “one long island at some point, carved from the mainland by a cataclysm the ancient ‘mythmakers’ would only hint at, and then cut into three,” and that the nearby North Berwick Law, just three feet shorter than Giza’s Great Pyramid, might have been “shaped” into the pyramidal form we now recognize it by. My theories, needless to say, have met with some amusement in certain quarters, and I’m told that one alternate researcher has been known to go for a few cheap laughs at my expense.

Nevertheless, I’ve since found two local folk tales that suggest a bit of “terraforming” might indeed have occurred.

- The Tale of the Saint: Legend has it that there once existed a rock that was a danger to shipping. A monk named Baldred miraculously moved it around the coast and out of harm’s way, creating a geological feature since known as St. Baldred’s Boat.

- The Tale of the Devil: One day the Devil was strolling up the surf, and so frightened a local woman that she let out a shriek. Startled, the Devil dropped his walking stick and splashed away. His stick shattered, becoming the three islands in my article. The nearby Bass Rock, upon which can be seen the ruins of Baldred’s Chapel, is also known as the Devil’s Hoof.

And then there are the lions.

Lying next to The Lamb is the sleeping lion that many see in the shape of Craigleith Island, and 20 miles to the west stands Arthur’s Seat, the sphinx-shaped extinct volcano that dominates Edinburgh’s skyline. A third lion may be seen in Scotland’s Royal Standard, the flag that shows a red rampant lion, and archaeologist Mark Lehner has established that the Great Sphinx was once painted red.

The fourth lion is found in the Legend of Lyonesse, the tale of a land that sunk beneath the waves off England’s southwest coast. Etymologically, however, the name has been traced as an alteration of the French word Léoneis, which itself developed out of Lodonesia, the Roman name for Lothian. North Berwick lies in East Lothian.

Within a day of Geller’s purchase a conversation began on the Cabinet of Wonders website. One poster duplicated my original graphic and confirmed that Sirius, the alpha star of constellation Canis Major, did indeed fall on Inchcolm Island, where Walter Bower compiled his Scoticronichon (Map 1, below). Interestingly, the poster discovered that the constellation’s beta star, often referred to as “The Herald” because it rises before Sirius, fell within Edinburgh, and wondered if the spot held significance. In fact, it fell on an area I knew well – an area named Starbank Park, which has a star cut out in the slope of its hill, flanked by two crescent moons, with a circular area above, presumably the sun. I have been unable to discover how the park was named, but it is not unlikely that Edinburgh’s Grand Lodge of Freemasons might have had a hand in it.

Inchcolm lies within sight of Starbank Park, and there is a local tradition that names it “Isle of the Druids.” Eighteenth-century intellectual Thomas Paine, in his treatise on “The Origin of Freemasonry,” claims that the fraternity’s roots are found in the solar-centric religion of the Druids, the priestly caste extant in Britain during the Roman occupation, driven underground by the rise of Christianity. Paine attributes the importance of freemasonic secrecy to fear, observing, “When any new religion over-runs a former religion, the professors of the new become the persecutors of the old. We see this in all instances that history brings before us,” and concludes that “this would naturally and necessarily oblige such of them as remained attached to their original religion to meet in secret, and under the strongest injunctions of secrecy. Their safety depended upon it.”

By far the most obvious freemasonic symbology, however, appears to be rooted in Egyptian cosmology, but the fraternity has forgotten why. Also, in Masonic ritual great emphasis is placed on Geometry, exemplified by the enigmatic “G” within the craft’s ubiquitous square and compass insignia, and on the cardinal directions of the geographic compass.

Frank C. Higgins’ 1919 “Ancient Freemasonry: An Introduction to Masonic Archaeology” states that the 23.5º angle and its 47º double are two of Freemasonry’s “Cosmic Angles,” and that they “are encoded on coins showing pre-Christian Phoenician temples of Cypress, ancient Greek paintings of Hermes and Ceres, as well as in the Masonic Keystone and Compass of the present day.”

To those two numbers we should add a third — 33 — the highest attainable degree of rank in Scottish Rite Freemasonry, as well as the number of the latitudinal line along which, for reasons unknown, many of the world’s sacred sites are located. Using these three numbers I have discovered an ancient message encoded by the pyramid builders. To understand that message, and its implications, we must first consider the Prime Meridian.

The Prime Meridian is an invisible line that stretches between the North and South Poles, which, due to the rotation of the Earth, passes the sun every 24 hours. It calibrates the hours of the day around the world, and begins the first of 360 vertical slices of one degree each. Its position is arbitrary, but in 1884 it was agreed that Greenwich, UK, should mark the International Prime Meridian, and it has done so ever since.

The Great Pyramid sits 31.08 degrees east of Greenwich, and researchers Scott Creighton and Gary Osborn have recently demonstrated that Freemasonry’s cosmic angles of 23.5 and 47 degrees, relating to Earth’s axial tilt, have been encoded in its internal geometry, and Osborn has found those same angles encoded in countless works of art over many centuries.

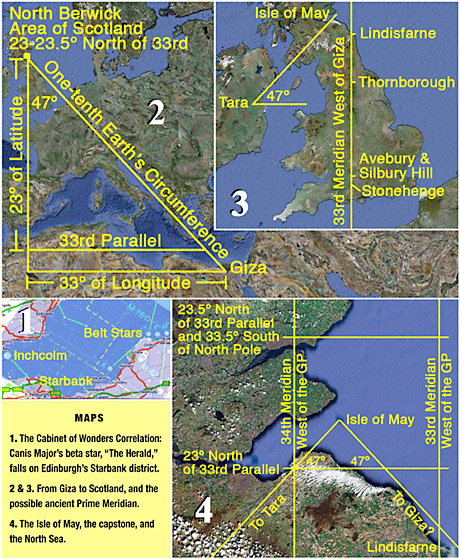

I decided that any civilization advanced enough to build the GP would likely have used its position to mark its own Prime Meridian. Then I counted 33 degrees to the west, to Morocco’s Atlas Mountains, and established that the meridian that today runs north to south through a point 1º 52´ West of Greenwich would, to the pyramid builders, have marked their own 33rd meridian. So I then drew a horizontal line between the GP and that point, and then another directly north along that ancient 33rd (Map 2). Incredibly, my second line all but kissed four major English sacred sites on its way to the north — Stonehenge, Silbury Hill, Avebury, and Thornborough, the huge three-henge complex confirmed as “the world’s first monument aligned to Orion’s belt stars” — before nearing the border of Scotland at the Holy Isle of Lindisfarne, perhaps indicating that this ancient 33rd meridian may have once been as sacred and important as today’s 33rd parallel, and possibly have been the Prime Meridian before Giza (Map 3).

But that’s when things got really interesting.

The four islands that had figured so mightily in my “Pyramids of Scotland” article — Orion’s Belt Star islands and the Isle of May — lay in the rectangle formed between the ancient 33rd and 34th meridians and the 23rd to 23.5 degree parallels north of today’s 33rd (Map 4). Astonishingly, using the three most significant Freemasonic numbers, two of which relate to Earth’s axial tilt, the geometry from the GP’s ancient Prime Meridian pointed the way to the North Berwick area and, once there, those same numbers helped enclose the area of the North Sea wherein my belt-star islands and The May lay. Even more incredible, I discovered that the line I had drawn between Tara and The May, seven years ago, followed a 47º angle, as did a line drawn from the eastern edge of Lindisfarne and The May, creating a 47º pyramid with The May at its apex — perhaps, symbolically, the GP’s missing capstone. Due to the enormous distance involved I have been unable to establish if the Lindisfarne line continues exactly to Giza, but I’d lay odds on it. And finally, I have calculated that the distance between the GP and North Berwick equals one-tenth the circumpolar circumference of the Earth.

The Isle of May that my original Orion Correlation pointed to was an important site of Christian pilgrimage in the middle ages. Recent archaeological excavations, however, have shown that the site has been in use since at least the Bronze Age. Could it be that the Great Pyramid, thought by some to be built by the survivors of the cataclysm that destroyed Atlantis, built the GP where they did in order to geodetically point the way back to their former homeland? Could it be that Princess Scota’s people, when they left Egypt, were not heading to parts unknown, but were simply heading home?

That inhabited land once existed between Scotland and Scandinavia has been confirmed by Exeter University’s Doggerland Project, named after the Dogger sandbank where prehistoric artifacts have been dredged up. Could the Isle of May have been anciently revered as the last remaining vestige of that sunken land yet remaining above the waves?

And could the Doggerland area have been just part of a much larger Atlantis?

Comyns Beaumont, in his 1946 “The Riddle of Prehistoric Britain,” speculates that Atlantis encompassed the entire British Isles, and that only some of it sank due to a comet strike that also tipped the Earth into its present-day 23.5º angle. Moreover, he says, the center of Atlantis lay on the Isle of Mull, off the west coast of Scotland. I have calculated that Mull is now precisely 23.5 degrees north of the present-day 33rd parallel and, if Beaumont’s comet-strike theory be given just a modicum of credence, would have then lain just a few miles to the west of the Straights of Gibralter, the Pillars of Hercules in Plato’s account of the sinking of Atlantis. Might not Plato have been hiding (yet ultimately revealing) the truth of things by couching his tale in geodesics? Might he not have just as surely been saying that Atlantis once lay just beyond where the Pillars of Hercules now lay, before it shifted 23.5 degrees to the north?

To sum up: There once was a land that sank beneath the sea due to a cataclysm that tilted the Earth’s axis into its present-day 23.5º angle — an event that was the source of all the world’s far-flung flood legends. The survivors built, or caused to be built around the world, huge structures that fixed their new location in the cosmos, and built the Gizamids to establish a Prime Meridian that mathematically memorialized an earlier Prime Meridian exactly 33º to the west, along which were built at least three of the best-known megalithic sites in Britain, thereby also encoding the location of their pre-deluvian homeland, 23.5º north of where it originally lay, and 33º south of today’s North Pole. What are the chances that the freemasonic numbers 23.5, 33, and 47 would lead us to a small patch of the globe containing three islands laid out in the pattern of Orion’s Belt, near a very pyramidal hill just three feet shorter than the Great Pyramid, only 20 miles to the east of a Sphinx-shaped extinct volcano with Arthurian connections, in a city that is the acknowledged world capitol of Scottish Rite freemasonry — all in a land with an much-decried Egyptian foundation legend? And finally, if we accept the dictum “form follows function” as an architectural law, we might recognize in the immense size and shape of the pyramids the ideal physical mass and form necessary to defuse the power of yet another mighty wave. Flood shelters, anyone?

In the 19th-century words of Thomas H. Huxley, a.k.a. “Darwin’s Bulldog” for his support of Darwin’s once-heretical ideas: “The known is finite, the unknown is infinite; intellectually we stand on an islet in the midst of an illimitable ocean of inexplicability. Our business in every generation is to reclaim a little more land.”

Ladies and gentlemen: Hail, Atlantis!